Well, We Failed.

We set out with ambitious plans but after a year of development, we’ve run out of cash and are shutting down Wattage. I hate to say it, but Wattage Inc. is no more.

I hate to say it, but Wattage Inc. is no more. We were unable to secure the additional investment we needed, so we’ve decided to close up shop and call it a day. That said, we did manage to secure a deal that allows us to return our investors’ money. So while we didn’t exactly birth a unicorn, at least it wasn’t a total loss.

There are a number of reasons why we failed, and I felt there might be some value in sharing what we learned through this experience. I suppose the first thing we should talk about is our pitch deck.

“Now That’s A Beautiful Pitch Deck”

The one piece of consistent feedback we received throughout this entire process was how nice our pitch deck looked. We often joked that no matter what happened with Wattage, I could at least take a job building decks for others. Obviously its contents didn’t do much to help build a successful business, but I figured it might be worth sharing nonetheless. It didn’t exactly follow the standard pitch deck format, and it was also described as “nowhere near as crisp and focused as required.” But at least it looks nice, right? Sigh.

It went through upwards of 6o revisions I think, and you can download the last version here.

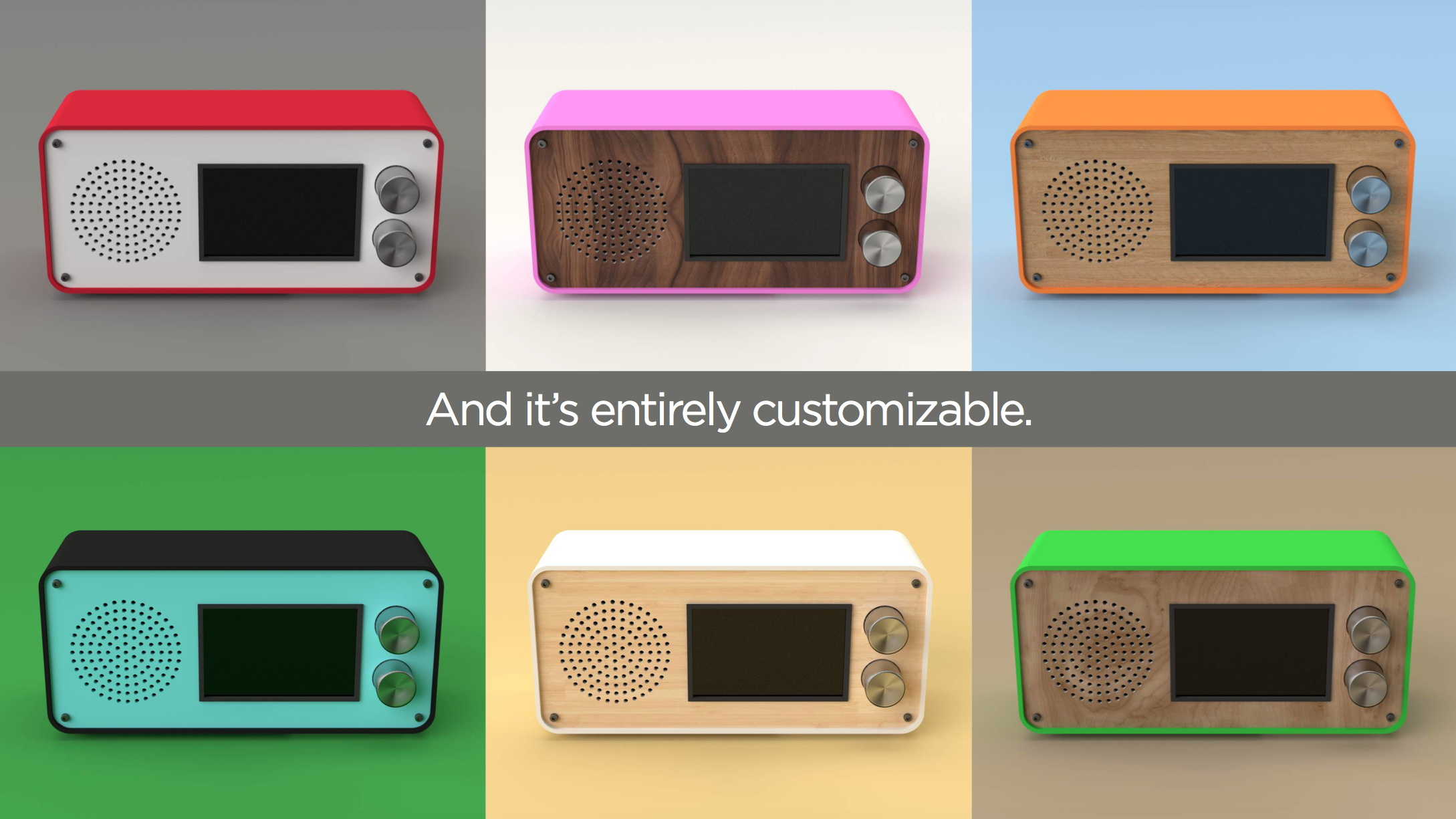

The vision for Wattage was a future where anyone could manipulate matter. Where we needn’t settle for the generic, mass-produced things that currently line store shelves. A future where we can easily upgrade our old devices instead of throwing them away. Or reprogramming them to do entirely new and useful things.

Here’s a working prototype, and a recent version of our software

We wanted to make it so creating and selling hardware was as easy as writing and publishing a blog post. You shouldn’t need to be an electrical engineer or an industrial designer to create electronic devices. Nor should you have to worry about supply chain or distribution if you wanted to sell them. We believed it was possible to eliminate all of that complexity, so the average person could easily create highly customized hardware without any electronics know-how, all within their browser.

Of course, things didn’t exactly play out that way. But why?

An Absence Of Traction

I suppose our failure can be summed up quite easily: An inability to show traction. We were attempting to create an entirely new market for mass-customized electronics, which we originally viewed as something positive (as we felt we could create and own this new market). But from a fundraising standpoint, it was the opposite. Why would investors put large sums of money into a company going after an unproven market? (Hint: they don’t.)

Being a hardware company, we focused on building prototypes to validate that our vision was technically feasible. In retrospect, this was a mistake. Instead, we should have released something far more lightweight, and as quickly as possible. Our efforts should have been focused on validating interest in our product and generating traction. We didrealize this, and we were moving to launch a beta as a means of validating interest. The problem is we realized too late, and ultimately didn’t want to launch a beta that we couldn’t afford to support.

Not Enough Focus

We had grand plans for the platform and we were only working on a small subset of features. But we should have been working on even fewer. We had decided to build the initial platform around just hardware creation. We wouldn’t offer the marketplace, or anyway to program devices, and customers would need to assemble their creations themselves. But that was still too broad a focus. Instead of trying to build a platform for hardware creation, we should have focused on selling a single but highly-customizable product. Doing so would have allowed us to prove that we could actually ship product to paying customers.

Poorly Playing The VC Game

While there are obviously a number of options for raising money, we chose the venture capital route. I knew this would be a difficult endeavour, but reading things like Venture Deals or all of Paul Graham’s essays do little to actually prepare you for how challenging it really is.

Having previously raised $250,000 from friends & family, we had set out to raise a $2M seed round. I spent the better part of 6 months meeting with VCs in San Francisco, Silicon Valley, New York, and Toronto. In the Valley, I was told we were raising too little. In Canada, we were raising too much. In retrospect, it looks like we attempted to raise too much, too soon. Instead of raising a large pre-launch seed round, we should have raised a smaller amount from angel investors. Raise a smaller amount, and release a smaller product. If we started generating traction, we could have then raised more.

To that end, I wish I would have taken better advantage of AngelList. There’s so much potential there. We created a profile and regularly updated it, but we never successfully used it as a fundraising platform.

What About Crowdfunding?

We got very close to launching a crowdfunding campaign, but ultimately decided against it because I felt it was premature for us. We didn’t have enough confidence in our product costs, so even if the campaign was successful, there was a good chance that we’d ultimately lose money on each sale. We’d always planned on crowdfunding, but I felt we needed to be further along before doing so.

How Does This Scale?

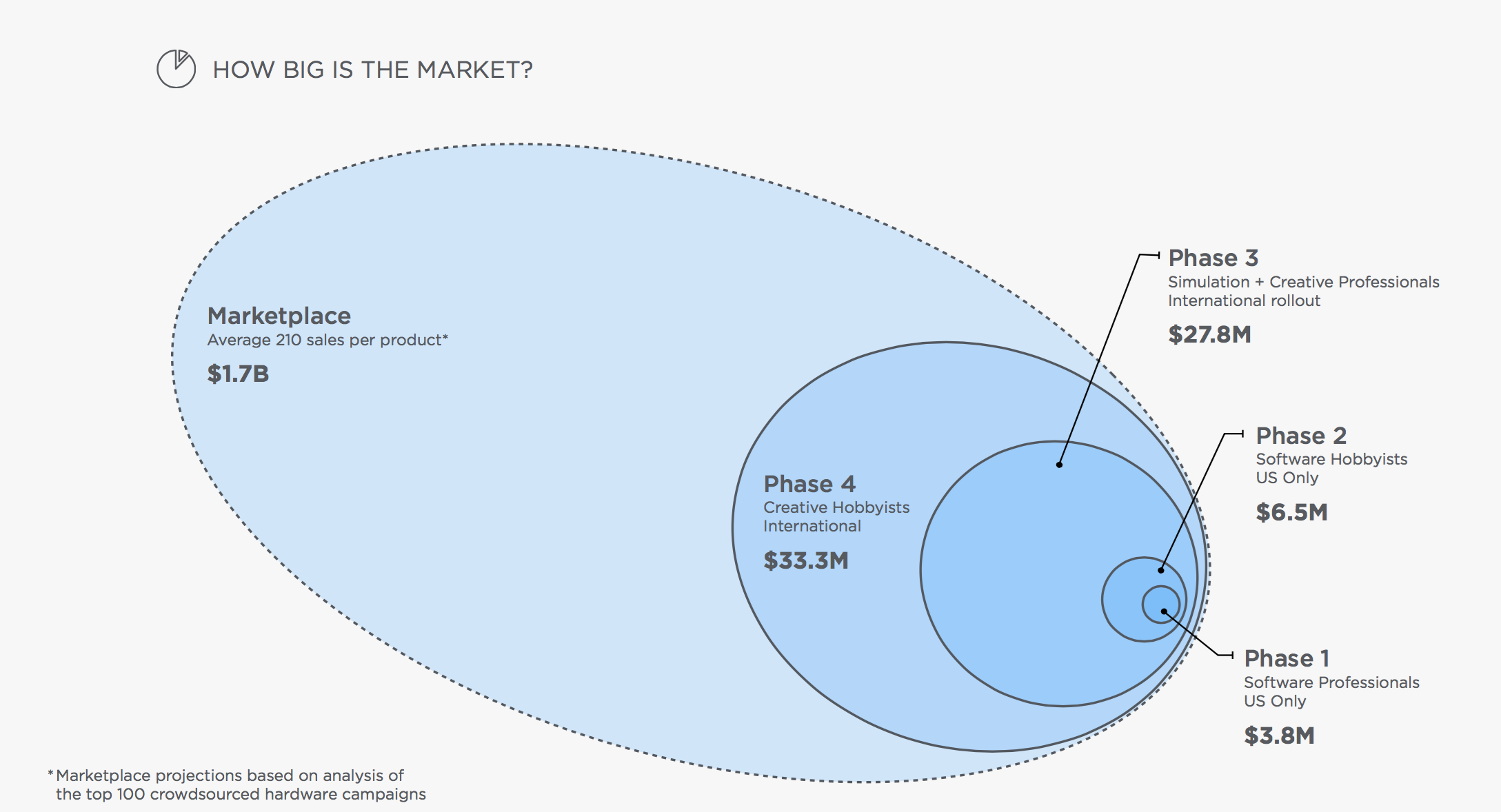

Our business model was about selling hardware. By reducing the complexity of creating hardware, our bet was that more people would create and buy. We would then wrap these creation tools in a marketplace, so creators could also sell their inventions to the masses.

In the earlier versions of our pitch deck, we focused a lot on empowerment. We were targeting software developers, as we believed we could offer them an entirely new outlet for their creative efforts. But this narrative wasn’t big enough. Investors want to hear a story about changing the world. Large ambitions, with a meaningful impact on the market, resulting in massive sales. We just didn’t tell a big enough story.

I also don’t think I properly emphasized the marketplace potential, as most investors got hung up on the number of potential creators. We looked at ourself as a diverse marketplace of mass-customized goods, but that potential (or at least as we articulate it) didn’t seem to resonate with investors.

We also heard concerns about the viability of scaling a bespoke hardware business. The manufacturing world is geared for mass-production, with profits coming from economies of scale. But we felt we could overcome this with standardized design & manufacturing tools, in distributed factories, using modular electronics. We saw huge potential in the long tail of things. But this was obviously unproven and we clearly didn’t do enough to reduce investor fear in our ability to pull this off.

We Were Too Early

1,600 people signup for our email newsletters, and each of them received a personal message from me. I gave them my email address and phone number, and invited them to chat if they had any questions. I heard from 100's of them, and many shared “the thing” they wanted to create. The problem is many of them simply weren’t feasible with the current technology. I suspect we could have eventually delivered on most of them, but not in the foreseeable future.

Furthermore, when I looked at the various prototypes we’d created, the quality simply wasn’t there yet. We were heavily using laser cutting as our means of fabrication, and while it allowed us to produce something close to our vision, it wasn’t good enough. What we really needed was a hybrid of laser cutting and 3D printing, but unfortuately 3D printing is still far too slow and expensive to be realistic. I have no doubts that 3D printing will play a huge role in the future of manufacturing, but it simply isn’t there yet.

So That’s It.

It’s been a fun ride to say the least. We’re still deciding what to do with everything we produced this past year. There’s a high likelihood Wattage will be reborn in another form sometime in the future, but we just don’t know yet.

I wanted to say thank you to those that supported us during this adventure:

Hot Pop for helping us design & create all of our physical prototypes

Cossette Lab for the office space, staff, and bagel Monday’s

Chris Tanner for the design help

Sam Dallyn for designing our logo

Jonas Naimark for creating this awesome animation

Heist for the design help

MakeWorks & Teehan+Lax for the office space in the early days

But the most thanks goes to our supporting wives, who consistently provided encouragement through all of the up’s & down’s. I wish this had turned out better than it did, but at least we’ll have actual paying jobs again! <cough>inquires welcome</cough>

So that’s it for now. If you’d like to reach us, you can find us on Twitter:

Andy MacDonald (@andymacd)

Brett Hagman (@BrettHagman)

Peter Nitsch (@peter_nitsch)

Jeremy Bell (@jeremybell)

Originally published on Medium, but republished here as I consolidate my writing on a self-hosted platform.